COVID-19 has been deadly to cancer, transplant patients, but antibodies can offer 'shield'

2/28/2022, Tom Corwin, Augusta Chronicle

Even though she has been vaccinated and boosted, Bridgette McClarty, 49, of Grovetown knows her cancer treatment likely wiped out all of her protection against COVID-19.

"I was walking around in a war with nothing," she said. Her doctors at Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University have since found a way to protect her through a new shot of monoclonal antibodies, but McClarty remains cautious.

"I still have my guard up," she said.

The pandemic has been especially hard on cancer patients and in particular on disadvantaged populations who already suffered unequal treatment and higher risk, according to the American Association for Cancer Research. A study of 73 million people found cancer patients were at five times higher risk of infection compared to those without cancer, according to the report. But Black patients with breast or prostate cancer were at five times higher risk for infection than white patients with the same cancers, the study found.

"This pandemic has really laid bare inequities in cancer care," said Dr. Ana Maria Lopez, chief of Cancer Services at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson Health in New Jersey. For instance, during the first phase of the pandemic, surgeries for Black prostate cancer patients decreased by 91% compared to 17.4% for white patients, she said.

"The data are very, very clear," Lopez said.

Those with blood-borne cancers like McClarty were at even greater peril than other cancer patients. Among 400,000 people infected with COVID-19, including more than 63,000 that had cancer, patients with cancers like hers had a 17% death rate compared to 7% for breast cancer patients.

Research pays off

Some of the impacts on cancer patients may not be felt for years. Between January and July of 2020 as the pandemic took off in the U.S., patients missed nearly 10 million cancer screenings. Researchers estimate there will be 2,500 additional deaths from breast cancer, a figure that could double if delays in treatment and screenings continue because of the ongoing pandemic. The National Cancer Institute predicted in 2020 that delays in screening and treatment would result in 10,000 additional deaths due to breast and colorectal cancer over the next 10 years.

In a paradox, cancer research helped to protect everyone else, the AACR said. Decades of research into a potential cancer vaccine and treatment using messenger RNA were harnessed by pharmaceutical companies to quickly create the COVID-19 vaccines, officials with AACR said.

"Years of discovery in cancer research and cancer-related fields have played a critical role in rapidly developing the COVID-19 vaccines that have been desperately needed during the pandemic," said Dr. Margaret Foti, CEO of AACR. Yet impacts from COVID-19, from shelter-in-place orders to diverted funding and resources, are likely to set back cancer research for years, the group reported. A survey of 200 cancer researchers found they expected the pandemic to set back their work at least six months on average and would delay breakthroughs by nearly 18 months.

Of all of those impacted by the pandemic, it is patients like McClarty who might be most affected. Bloodwork at her primary care doctor revealed an elevated white cell count, and a biopsy in March 2021 revealed she had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, an aggressive cancer that can grow quickly and can be fatal within months if untreated.

She was referred to Dr. Vamsi Kota, director of the bone marrow transplant program at Georgia Cancer Center, and he immediately put her in the hospital for more tests. Unfortunately, her cancer also had Philadelphia chromosome, a marker that meant hers was even more aggressive and would not respond well to standard chemotherapy. She opted instead for a clinical trial that she would stay on for the next nine months.

"I want to narrow that gap of knowledge," McClarty said. Ultimately, her treatment would require a stem cell transplant, and there her luck changed. Her sister, Bercedia Stewart, matched up perfectly with her on all 12 markers they look for in a donor.

That "is uncommon, particularly in the Black community,” where it can be tougher to find a donor match, McClarty said. The transplant happened on Dec. 23.

"That was my re-birthday," McClarty said.

'Like putting on armor for battle'

Unbeknownst to her, she was being shielded at the hospital by something that began nearly two years before, when COVID-19 first hit. Recognizing the potential risk to patients, doctors and the hospital leadership decided to immediately wall them off from other patients to lower the risk of exposure, Kota said.

"Through the two years, we have segregated the cancer floor very well, the transplant floor especially, and we needed a lot of support from the leadership to keep that going," he said. "We did not allow other patients, even if they were COVID-negative, to be on the transplant floor."

As it turned out, there was a very serious reason for that.

"Transplant patients actually have the highest probability of dying from COVID, 30% in some studies," Kota said, because they are so immunocompromised.

With those and other measures in place, the transplant program actually thrived and has done the highest number of transplants it has ever done, Kota said. The outcomes have been outstanding as well — where 65-70% nationally are expected to survive one year, Georgia Cancer's rate was 82% in 2020, he said.

"We did much better than expected and that is because of the tremendous initiative that has been undertaken by multiple levels of people," Kota said. It is even more remarkable considering it happened in the first year of the pandemic, before vaccines and treatments like monoclonal antibodies were available, he said.

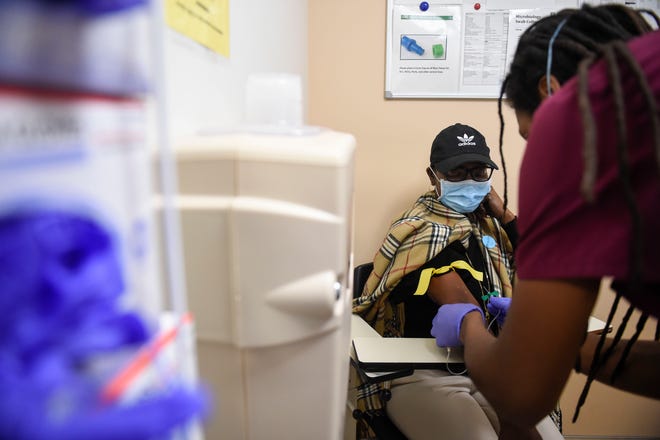

Yet even with the vaccines, those patients are unlikely to mount an effective immune response. It is why AU Health System began giving many of those patients a therapy called Evusheld, a monoclonal antibody that is a combination of two drugs and can be given by injection, said Dr. Phillip Coule, chief medical officer for AU Health. It can be a preventive treatment that should last for months, he said.

"We can use this monoclonal antibody essentially to buy them six months of protection," he said. It is one of the ways the center can look out for them, Kota said.

"This does give both them and us a sense of security that we limited their risks further," he said.

For McClarty, it is like putting on armor for her battle against infection.

"I didn’t walk into a war without at least a shield," she said.

Should she make it a year, patients like McClarty do very well, Kota said.

"In the case of transplant, they have a very high chance of cure," he said. But after that one year, some of them did get COVID-19 and die, and that's been tough, Kota said.

"They handle the hardest parts of the leukemia and the transplant and more than a year out of transplant, they are essentially cured of their disease," he said. "Then when they die of COVID and COVID-related complications, it is such a disheartening thing for the family and for us as the health care team."

View More